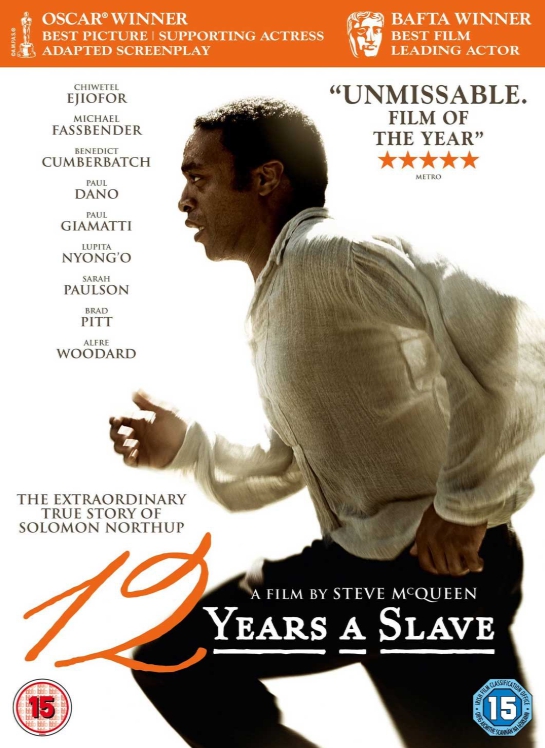

What the Film Is About

“12 Years a Slave” is a harrowing depiction of one man’s forced journey through the agony of slavery in pre-Civil War America. The film is less an adventure or survival story than an unflinching examination of human endurance and dignity under relentless dehumanization. At its core, it follows Solomon Northup, a free African-American man kidnapped and sold into slavery. The emotional arc is one of intensifying despair, punctuated by rare moments of hope and solidarity. The movie invites audiences not only to witness but to feel the terror, resilience, and longing of an individual robbed of name, home, and agency.

The central conflict is both external and internal. Externally, it is Solomon’s struggle against the brutal machinery of chattel slavery. Internally, it is his determination to hold on to his identity, sense of self, and humanity in a system designed to annihilate them. Rather than presenting a neat narrative closure, the film confronts viewers with the ongoing violence of this era, gesturing toward a much broader social trauma.

Core Themes

The film’s most penetrating theme is the corrosive power of institutionalized racism and the systematic denial of personhood. “12 Years a Slave” explores how slavery is not only a political or economic system but also a moral and psychological catastrophe. The story interrogates power: its gross abuses, its mutating forms, and the responses of those subjected to it, whether through resistance, complicity, or resignation. The helplessness inflicted by arbitrary power becomes a source of deep existential anguish and moral crisis for all involved.

Identity is another crucial theme—one’s self-definition constantly threatened by circumstances and violence. For Solomon, the effort to maintain his identity as a husband, father, and free man becomes a revolutionary act in itself. The film also examines the moral costs of survival within an oppressive regime. Characters must navigate impossible choices, revealing the tragic complexity of loyalty, betrayal, and self-preservation.

Upon its release in 2013, the film resonated with contemporary conversations about race, memory, and the legacy of slavery. In an era grappling with systemic racism and the need for historical reckoning, “12 Years a Slave” was both a corrective against sanitized narratives and a forceful call to acknowledge the personal, generational wounds left by such histories. Its themes remain painfully relevant amid ongoing global debates about racial equity, justice, and the long shadow cast by past atrocities.

Symbolism & Motifs

Director Steve McQueen uses deliberate symbolism and visual motifs to reinforce the film’s themes. Repeated images of chains, ropes, and the act of stripping away clothes serve as visual shorthand for the stripping of identity and autonomy. The motif of music and violin-playing alludes to Solomon’s individuality and creative spirit, surviving even amid dehumanization. The frequent juxtaposition of breathtaking southern landscapes with acts of brutality underscores the jarring coexistence of beauty and horror, suggesting the ways violence underpins even the most idyllic facades.

Trees and nature often function as silent witnesses to atrocity, symbolizing both endurance and the impartial record of suffering. The camera’s lingering gaze in scenes of violence is not simply gratuitous; it draws attention to the complicity of all who look away, past and present. The recurring motif of names—denied, changed, or forgotten—highlights both personal erasure and the persistent struggle for recognition. The physical objects—letters, musical instruments, books—stand in for lost freedoms and aspirations, carrying deep emotional resonance in fleeting moments of hope.

Key Scenes

Key Scene 1

One of the film’s most emotionally arresting moments is when Solomon is forced to participate in the beating of another enslaved person. This scene crystallizes the horror of a system that not only brutalizes bodies but enlists the oppressed in the apparatus of their own subjugation. The long, unbroken take emphasizes the agony and helplessness of the characters, as well as the silence and complicity of the bystanders. More than a depiction of violence, the scene functions as a meditation on the destruction of agency and the profound moral dilemmas imposed by survival within a cruel system.

Key Scene 2

A pivotal scene comes when Solomon risks his life by asserting his identity and autonomy—whether through a fleeting act of rebellion or asserting that he once was a free man. This assertion is fraught with peril but is crucial in developing the theme of identity; in a world bent on his erasure, every act of self-assertion is costly, dangerous, and deeply meaningful. The film makes clear that survival is not only physical but moral: reclaiming one’s voice and story is an act of resistance against the stripping away of humanity.

Key Scene 3

The film’s closing reunion scene, where Solomon returns to his family, serves as both a moment of catharsis and a final statement on the irrevocable consequences of trauma. While it could be read as a triumphant homecoming, McQueen frames it with restraint and sorrow, acknowledging that the wounds and absences left by enslavement are permanent. The awkwardness and grief present in this scene evoke the devastating cost of lost years and underscore how slavery inflicts scars that echo across generations. Rather than fulfilling a traditional narrative of redemption, the scene insists on the gravity of what was stolen and what can never fully be restored.

Common Interpretations

Most critics and viewers interpret “12 Years a Slave” as a powerful denunciation of slavery’s inhumanity and a searing testament to Black resilience in the face of unimaginable suffering. It is frequently discussed as a corrective to American historical amnesia: a work that refuses to turn away from pain or clean up the past for the sake of comfort. Many see the film as not only about the horrors of slavery but about the legacies of trauma—how violence haunts individuals, families, and national consciousness.

A significant thread in interpretation concerns the film’s refusal to offer simple catharsis. Instead, it lingers on the discomfort and ongoing consequences of systemic racial violence. Other interpreters focus on how the film universalizes the struggle against dehumanization, making its historical specifics resonate with broader issues of injustice, oppression, and endurance worldwide.

Some viewers debate how the narrative centers a literate, educated protagonist—suggesting this was necessary for mainstream audiences to empathize, but also raising questions about which stories get told and remembered. Still, the prevailing view holds that the film’s emotional honesty and directness make it essential viewing for anyone seeking to understand the realities and aftereffects of American slavery.

Films with Similar Themes

- Schindler’s List (1993) – Explores systemic atrocity and human resilience within the Holocaust, connecting through its focus on suffering, survival, and moral choices under dehumanizing regimes.

- Roots (1977) – Dramatizes the African-American experience from enslavement through freedom, paralleling the multigenerational trauma and loss of identity central to “12 Years a Slave.”

- Amistad (1997) – Focuses on an earlier legal fight for freedom by kidnapped Africans in America, raising similar questions about justice, personhood, and the fight against an entrenched oppressive system.

- Hotel Rwanda (2004) – Addresses genocide, survival, and moral choices during the Rwandan conflict, echoing themes of powerlessness, complicity, and the assertion of humanity in the face of systemic brutality.

Ultimately, “12 Years a Slave” communicates a profound and painful truth about both human nature and society: our capacity for cruelty is nearly boundless when protected by systems of power, but so too is the resilience of those who endure, resist, and remember. The film stands as a testament to the enduring impact of historical trauma, urging viewers to confront both the specific horrors of American slavery and the universal dangers of forgetting or minimizing such legacies. Its lasting significance lies in its demand—for empathy, for vigilance, and for the hard work of reckoning with the past.